Introduction

Ice (image credit to John Goodenough)

“Brandon. Yes. Brandon would know what to do. He always did. It was all meant for Brandon. You, Winterfell, everything. He was born to be a King’s Hand and a father to queens.” (“Catelyn II”, A Game of Thrones)

By the time A Song of Ice and Fire begins, Brandon is nearly 20 years dead; the only physical memory remaining of the onetime heir to Winterfell is the solemn statue of him in the ancient seat’s crypts. Brandon is remembered for his hot-headedness and quick temper – that particularly Stark “wolf’s blood” which led him and his sister Lyanna to early graves. What is often overlooked with Brandon, however, is how southron the heir to Winterfell had become by the time of his fateful meeting with King Aerys. From a young age, Brandon – under his father’s watchful eye – had been steeped in southron-looking and overtly southron customs: a competent jouster, friend to riverlords and Valemen, with a young squire and a Tully fiancée, Brandon was almost indistinguishable from the heir to any great southron seat. What would distinguish him was the inborn Northern vengeance that – combined with southron modes of chivalry – drove him to challenge a grievous crime against his sister, with fatal results.

Born to Greatness

Brandon was born in 262 AC, the eldest son of Lord Rickard Stark and his wife, Lyarra. Though Stark lords – indeed, most paramount lords in Westeros – tended to marry the daughters of their bannermen, Rickard’s consort was rare in sharing her husband’s Stark name: they were, in fact, first cousins once removed, Lady Lyarra being the daughter of “the Wandering Wolf” Rodrik, brother to Rickard’s grandfather Willam. Few marriages in Westeros are made on personal grounds alone, and even if the lordly couple personally liked one another (there is no evidence to say either way), the political advantage behind their marriage was clear. Since the death of Rickon Stark, son and heir of Cregan the One-Day Hand, the Starks had faced a long succession crisis, with multiple heirs claiming Winterfell (and multiple Lords of Winterfell dying in a short period of time). Much like the Laenor-Rhaenyra match before the Dance of the Dragons, or the Aegon-Jaehaera match afterward, this marriage was intended to bind up two competing claims into one, a neat closing of ranks within the Stark lineage.

It was, perhaps, in this spirit that Rickard and Lyarra gave their first son the very traditional Stark name of Brandon. Every generation of Starks was by custom supposed to have a Brandon – in tribute to that most venerated of Northern heroes, Brandon the Builder – but no Brandon Stark had actually ruled Winterfell since a son of the One-Day Hand. By naming his eldest son Brandon, Rickard sent a clear sign to his vassals and distant cousins alike that his successors were the true heirs of Winterfell. In our own world, Henry VII of England used a similar tactic on his own elder son. With his claim to the throne shaky indeed, built on conquest and bastard-line foundations, the king named his eldest child Arthur after the fabled hero-king of Britain from whom the Tudors were supposedly descended; that connection to English mythology gave Henry a convenient political narrative for his reign which his dubious background lacked. Rickard was much more certain in his possession of Winterfell, but he knew as well that any remaining trueborn descendants of Serena and Sansa Stark, the daughters of Cregan’s heir Rickon, had a better right to the ancient Stark seat than he did; a move of deeply political symbolism could help quell any latent unrest about his line’s right to rule.

Baby Brandon was not long alone in the nursery; two more brothers and a sister followed in rapid succession. His life should have been set in a familiar pattern, following the example shown by his nephews Jon and Robb later: lessons with the maester, time spent in the practice yard with Winterfell’s master-at-arms, some travel to the courts of his father’s bannermen, and eventually a wife selected from one of the best Northern families – in short, the most conventional upbringing for a paramount lord’s heir. It was designed to familiarize him with his territory and vassals, to ensure that he could keep the king’s peace in the semi-independent North.

Lord Rickard, however, had no patience with such a conventional, politically distant future for his family – especially his heir. Young Brandon would instead be an important pawn in his scheme of “southron ambitions”, allying the North to the rest of the realm in a way not seen in the history of the united kingdom. Indeed, Brandon himself would enthusiastically adopt his father’s ambition, becoming a more southron lord than any of his predecessors.

The Northman Looks South

Lord Rickard began Brandon’s southron-izing early. The Lord of Winterfell decreed that his heir would be fostered with the Dustins, the vassals who ruled Barrowton. Brandon would spend his formative years in the Dustins’ ancestral seat.

Fostering was no new strategy for the lords of Westeros; the practice of fostering children (specifically sons) with other lords can establish loyalty and good relations between the fathers and forge lasting alliances between houses:

“Horas was to come with us in your place, whilst you remained in the Arbor as Lord Paxter’s page and cupbearer. If you had pleased him, you would have been betrothed to his daughter.” (“Samwell II”, A Feast for Crows)

Fostered sons would ordinarily go to a lord from the same regional kingdom of Westeros, as the above quote from Randyll Tarly notes: Jaime Lannister fostered with his father’s vassal Sumner Crakehall, for example, and young Doran Martell with his mother’s vassals at Salt Shore. So it would have been little surprising to the men of the North to hear that the heir to Winterfell would be fostered with a Northern vassal house (less surprising, certainly, than Rickard’s later move of sending his second son Eddard to Jon Arryn in the Eyrie). The Dustins, onetime Kings of the Barrowlands and now rulers of prosperous Barrowton, were old Northern blood, an able choice to nurture the future wolf lord.

It may have been, in fact, the Dustins’ shrewd stewardship of Barrowton which attracted Lord Rickard to send his heir there. White Harbor might be the North’s only true city, but Barrowton (along with Winterfell’s own winter town, a largely seasonal establishment) is its largest town, and the only town in the southwest of the North. Barrowton’s wealth is likely not great, given its wooden (rather than stone) walls and lack of a royal charter, but it would still be an attractive commercial spot, perhaps drawing the west coast trade White Harbor would likely not see. Indeed, Barrowton would be a natural first stop for overland trade coming from southron Westeros up the Neck. In a relatively cosmopolitan environment, young Brandon would experience more southron exposure than a fostering elsewhere in the North (save perhaps with the Manderlys) might allow.

Part of Brandon’s training during his fostering also reflected Rickard’s southron ambitions for his elder son. During his time of fostering, Brandon likely became a knight; he certainly excelled in learning the knightly arts of jousting and swordplay. Knights are rare beyond the Neck, although not unknown: in White Harbor, for example, where the expatriate Manderlys and Faith of the Seven rule, knights can be found among highborn and low alike. Barrowton, however, is particularly noted for knighthood, with “barrow knights” remarked on as a fighting force by Maester Luwin. Certainly as well, the only member among Ned Stark’s Tower of Joy party specifically noted as a knight was Ser Mark Ryswell, of the Dustin’s close neighbors, the Ryswells (though Lord Willam Dustin may have also been a knight). Rickard may have appreciated the possible chivalric influence in the barrowlands and Rills – another reason, perhaps, to choose Barrowton for Brandon’s fostering. A future Stark lord, trained in chivalry, would certainly appeal much more to the southron Westerosi with whom Rickard hoped to broker powerful alliances.

Young Brandon applied himself well to the martial aspect of knighthood. Like many northmen, Brandon was an excellent horseman, and his riding ability surely helped his training for the lists. Jaime Lannister, a notably skilled tourney knight himself, acknowledged that jousting was three-quarters horsemanship; the slim but skilled horseman Loras Tyrell is an example of the power horsemanship can have in one’s jousting skill. Combined with his natural talent, Brandon honed his horsemanship skills with frequent rides in the Rills:

“Brandon was fostered at Barrowton with old Lord Dustin, the father of the one I’d later wed, but he spent most of his time riding the Rills. He loved to ride. His little sister took after him in that. A pair of centaurs, those two.”

(“The Turncloak”, A Dance with Dragons)

Swordplay also played a key role in Brandon’s young life:

“Brandon loved his sword. He loved to hone it. ‘I want it sharp enough to shave the hair from a woman’s cunt,’ he used to say. And how he loved to use it. ‘A bloody sword is a beautiful thing,’ he told me once.” (“The Turncloak”, A Dance with Dragons)

Even the most petty Westerosi lords know that skill with a sword is an essential component of lordly training. Brandon, though never noted as an eager student of history, had reason to note the failures of the dreamy, unwarlike Aenys I against the Faith Militant, and the memory of the weak Aerys I abandoning the North and Westerlands to deal with the ironborn perhaps still rankled in the breasts of northmen. Moreover, Rickard himself had fought in the War of the Ninepenny Kings, not merely as a soldier but as the Warden of the North, head of the Northern forces. Someday Brandon would take up than mantle along with the seat of Winterfell, and when war came again, Brandon would need to be ready to fight alongside his vassals and levies.

Who would have knighted Brandon is unknown (old Lord Dustin is a likely possibility, as is Ser Mark Ryswell), yet what is known is the identity of Brandon’s squire. A newly minted knight’s reputation, according to Barristan Selmy, depends in part on the honor of the man who conferred on him his knighthood, and for a northman, no greater honor would be than to receive knighthood from the heir to Winterfell and future master of the North. Why Brandon (or his father) chose a Glover of Deepwood Motte for his squire is not clear. Young Ethan was presumably a relative of Brandon’s great-grandfather Willam’s wife Lyanne Glover, whose only son had died young; perhaps the choice of Ethan was a favor to the Glovers’ frustrated ambitions with the Stark lineage. It may be as well that Brandon, with his possible western trade exposure and later friendship with a Mallister, wanted to cultivate a western-coast coalition, perhaps for future action against the ironborn. It may also be simply that Ethan was available and willing, in the largely un-chivalric culture of the North, to take on the southron role of knightly squire.

Life, of course, was not all training – or all chivalry – for the young heir to Winterfell. His rides in the Rills had doubtless taken him past the seat of House Ryswell, which ruled the area. Indeed, with Brandon such a devoted horseman, and the Ryswells marked for their horsemanship (with a horse head for their sigil and Rodrik Ryswell giving Willam Dustin a stallion as part of Barbrey’s dowry), it is very probable that Brandon spent a good amount of time, when not in Barrowton, with Lord Rodrik and his family. That family included Rodrik’s maiden daughters, Bethany and Barbrey; elder sister Bethany would go on to wed Roose Bolton, but Barbrey was still seemingly unattached at the time of Brandon’s visits:

“[M]y lord father was always pleased to play host to the heir to Winterfell. My father had great ambitions for House Ryswell. He would have served up my maidenhead to any Stark who happened by, but there was no need. Brandon was never shy about taking what he wanted.” (“The Turncloak”, A Dance with Dragons)

No Ryswell had wed a Stark in the past sesquicentury, but Stark lords and heirs had traditionally wed their bannermen’s daughters. The heir to Winterfell was naturally the greatest prize any noble maiden of the North could gain, and with Brandon’s strong ties to Barrowton and the Rills, Lord Ryswell might have supposed a further sign of favor from Rickard to his southwestern vassals was in order. Barbrey may be exaggerating in saying her father would offer her maidenhead to any Stark, but Rodrik may have honed in on Brandon’s chivalric training for his personal ambition: perhaps Lord Rodrik hoped that Brandon, compelled by honor, would take Lady Barbrey to wife after claiming her virginity.

Handsome, self-assured Brandon might have been gratified to have a well-bred maiden for his pleasure, although how much he truly loved Lady Barbrey is unknown. Still, he appeared to be little bothered by the idea of deflowering the daughter of his father’s bannerman (and his future vassal as well), although he had reason to know from history that a woman’s value in Westeros is directly related to her virginity at the time of her marriage. Perhaps Barbrey, like her father, presumed that Brandon would marry her after they had slept together; neither were betrothed at the time, and the lenient attitude expressed by Harwin toward Brandon’s brother’s alleged romance at Harrenhal may well have applied here:

“Words or kisses, maybe more, but where’s the harm in that? Spring had come, or so they thought, and neither one of them was pledged.” (“Arya VIII”, A Storm of Swords)

One cannot say whether Brandon entertained the idea of marrying Barbrey at this moment. Soon, however, he would not have a choice. His father had grander plans for his son:

“ … Rickard Stark had great ambitions too. Southron ambitions that would not be served by having his heir marry the daughter of one of his own vassals.” (“The Turncloak”, A Dance with Dragons)

Brandon the (Alliance) Builder

As Brandon matured, his responsibilities as the leading pawn in Rickard’s southron ambitions became larger. Brandon would be Lord of Winterfell, a cornerstone of a large pan-realm alliance, and the alliances he would make as a young man would reflect that future. On his own, and at Rickard’s direction, Brandon would start to become the coalition leader his father imagined, a southron-thinking Stark lord.

Alliances through friendships are certainly nothing new in Westeros. In a feudal system, monarchy and lordship is inherently personal; the ability of a lord or king to inspire personal loyalty in his vassals and men is one of the key factors to a successful rule. Friends made in boyhood, as fellow pages and squires, and the companions of young knighthood can become firm components of alliances later. Edmure Tully, as the young heir to Riverrun, befriended the sons of his father’s bannermen, Marq Piper and Patrek Mallister. They were similar young men in personality, as bold and hot-headed as Edmure himself, yet they were also politically important; as heirs to Pinkmaiden and Seagard, respectively, Marq and Patrek would prove crucial to Edmure’s having a stable reign as Lord Tully. Likewise, as a young man, Prince Aerys befriended his two fellow pages at court, Tywin Lannister and Steffon Baratheon, future paramount lords of the westerlands and stormlands, respectively; later, Tywin would become Aerys’ first choice as his Hand, and even later Aerys would look to Steffon for the same role when he grew to mistrust Tywin. Even Prince Rhaegar, never an overly friendly sort himself, recognized the value in having politically important companions: his circle of friends – including the venerable Kingsguard knight Arthur Dayne, Lord Jon Connington, and his Mooton and Lonmouth squires – gave Rhaegar a political cushion against the sycophantic lords who huddled around his father Aerys.

Rickard, certainly, knew the power of coalition building. As a commander in the War of the Ninepenny Kings, Rickard had witnessed a gathering of forces from all over Westeros unseen in the history of the realm. For the first and perhaps only time, lords were able to meet and ally with men to whom ordinary circumstances would never have introduced them (indeed, it may well have been in this war that Rickard first broached the idea of a power bloc with Hoster Tully and Jon Arryn). Not every generation would have a continental war in which to befriend the lords and heirs of other realms, but even peacetime could offer opportunities for the kinds of friendships that would translate into important adult alliances.

Accordingly, the companions Brandon brought with him to face Rhaegar in King’s Landing reflect his greater sense of Northern lordship in the context of the realm:

“Ethan Glover was Brandon’s squire,” Catelyn said. “He was the only one to survive. The others were Jeffory Mallister, Kyle Royce, and Elbert Arryn, Jon Arryn’s nephew and heir.” (“Catelyn VII”, A Clash of Kings)

The house identities of these friends demonstrates the connections Brandon was already building to cement the alliances begun by Rickard and the elder lords, his own father’s alliance network writ small. The Mallisters are one of the most important riverlord families, guardians of the west coast entrance to the Riverlands, with their seat at Seagard a fortress specifically built to repel the reavers of the Iron Islands. Jeffory Mallister may or may not have been the heir to Seagard, but his family’s reputation preceded him, and any lord wishing to keep friendship with the riverlords could do worse than to befriend the influential Mallisters. Before Brandon had wed his Tully bride, he was already looking to shore up the Riverlands alliance by courting one of its most distinguished families.

His friendship-based alliances also stretched to the other side of the realm. Brandon’s younger brother Eddard was fostered with Lord Jon Arryn, but Brandon himself would also secure the next generation of support among Vale families. Kyle Royce was part of that next generation, though it is not clear whether Kyle belonged to House Royce of Runestone or the junior branch of House Royce. If the latter, Kyle may have been a cousin of Brandon’s, perhaps a descendant of that Jocelyn Stark who had married Benedict Royce; if the former, Kyle was the descendant of the last First Men Kings of the Vale, longtime powerful vassals to the Arryns. In either event, the Royces were important friends for any lord looking to the Vale to make. Few events had ever happened beyond the Mountains of the Moon without some Royce influence: the Lord of Runestone had gathered forces to drive the rebellious Jonos Arryn out of the Vale, and Yorbert Royce had served as Lord Protector of the Vale for young Lady Jeyne Arryn and represented her at the Great Council of 101 AC.

More important to the Vale alliance, however, and the highest ranking of all his friends was Elbert Arryn. Young Elbert was the nephew of Lord Jon, and heir to the Eyrie after his childless uncle. If Rickard and Jon were allies now, Brandon was ensuring that he and Elbert would continue to be when both came into their paramount lordships; there would be no blood ties between the Arryns and any of the other houses in the “southron ambitions” pact as of yet, but Brandon was working to ensure that the Vale was not forgotten in the power bloc. These two future-Lords Paramount would pass on a two-generation-long alliance that could signal larger, even permanent ties between the North and the Vale.

The most important piece for alliance building, of course, was Brandon himself; an heir’s hand in marriage had always been a powerful piece to dangle before potential allies, and no less so with the heir to Winterfell. Accordingly, Rickard had brokered a brilliant match for his son: Brandon would wed Catelyn Tully, the elder daughter of Lord Hoster. True, Brandon’s grandfather Edwyle had wed a Blackwood, as had the Old Man in the North, but a betrothal between the children of two paramount lords was largely unprecedented, and certainly so for the Starks.

Almost three centuries prior, however, a Stark had been wed to another paramount lordly house – and that marriage scheme, like Rickard’s for the southron ambitions power bloc, sought to bind diverse realms into a strong union. Queen Rhaenys, sister-wife to Aegon the Conqueror, had arranged a match between a daughter of Winterfell and Ronnel Arryn, the King Who Flew. By arranging a match between the Lord of the Eyrie and a Stark maiden, Rhaenys demonstrated that those who had accepted Targaryen rule peaceably would in turn be supported by the dragons under the fledgling regime; a marriage between two former royals would strengthen both houses greatly, and the spouses’ gratefulness to Rhaenys would – hopefully – be pressed upon their children, creating a generation which owed its very existence to the Targaryen royals. Similarly, Rickard, Hoster, and Jon hoped to use their children (and, in Robert Baratheon, their ally) to bind four of the realms of Westeros into a united power bloc, mixing the blood of Starks, Baratheons, and Tullys to create a new generation of uniquely allied lords.

It is unclear what Brandon thought of his fiancée. The choice of his companions had demonstrated his interest in building southron alliances, and that interest (and his early training in his fostering) would have given him an appreciation for a bride who had all the courtly manners of a southron lady. Personally, as well, Catelyn was very pretty, and certainly attracted to him; as had already been demonstrated with Barbrey Ryswell, Brandon could be gratified by having the devotion of a pretty maiden. His betrothal, of course, would not make him a committed monogamist; Brandon, like most Westerosi lords, seems to have taken the attitude that as long as affairs are committed with discretion and bastards kept hidden, wives are to turn a blind eye to them. Nevertheless, he was likely not displeased with his father’s choice: Catelyn could be everything he wanted in a lady wife – southron-trained, graceful, beautiful, and devoted – and a crucial piece to his role as a southron-looking Stark lord.

The Gallant Fool

Brandon had received a southron-style fostering, had likely been knighted and taken a squire like any southron lord’s son, had made key friendships with southron lordlings like himself, and had become betrothed to the pretty daughter of a paramount southron lord. Had history not changed dramatically as it did, Brandon would have come into his inheritance in due course and continued the southron ambitions started by his father and the older generation in his power bloc, perhaps arranging more matches among his and Catelyn’s children and the children of Elbert Arryn or their Baratheon first cousins. Yet fate would not be so kind to Brandon, or to his father’s southron ambitions.

In 281 AC, Lord Whent hosted a great tourney at Harrenhal. That Brandon would attend was without question: Rickard was cognizant of the opportunity to show off the pawns of his southron ambitions to the rest of Westeros (especially at an event as enormous and well-attended as this grand tournament), and Brandon himself would not pass up the chance to test his jousting skills against the splendid competitors there (especially since the low population, vast size, and dearth of knights in the North makes regular tourneys there virtually impossible). While his fiancée Catelyn Tully seems not to have attended, Brandon could still demonstrate to all the proud southron lords that he was an able, cosmopolitan future ruler of the North.

Brandon did compete, although he did not win; Crown Prince Rhaegar, a highly skilled jouster himself, defeated the heir to Winterfell sometime into the five days of tilts. If Brandon was angry at his failure to beat the dreamy Prince of Dragonstone, his reaction would have been overshadowed by what happened at the end of the tourney. After defeating the veteran Kingsguard knight Barristan Selmy, Rhaegar received the crown of blue winter roses, meant to honor the Queen of Love and Beauty of his choosing. Then, spurring past his wife, Rhaegar laid the crown in the lap of Brandon’s sister, Lyanna.

Not for nothing would Brandon’s middle brother call this the moment “when all the smiles died”. Rhaegar had, in front of virtually the entire assembled nobility of Westeros, broken a fundamental rule of chivalry. Unsurprisingly, naturally hot-headed Brandon reacted almost violently:

Brandon Stark, the heir to Winterfell, had to be restrained from confronting Rhaegar at what he took as a slight upon his sister’s honor, for Lyanna Stark had long been betrothed to Robert Baratheon. (“The Targaryen Kings: The Year of the False Spring”, The World of Ice and Fire)

Brandon was naturally wild, but his reaction spoke both to his Northern honor and his training in chivalry. By rights, the crown should have gone to Princess Elia, who was both Rhaegar’s wife and, as crown princess, the highest-ranking woman present at the tourney. In offering the crown to Lyanna, Rhaegar had made a public declaration of romantic interest in a maiden who was daughter to one of his future bannermen and the betrothed of another. In effect, Rhaegar appeared for all the world to be claiming Lyanna as a royal mistress, in the style of his ancestor Aegon IV – a move which earned no love from the brother who was fiercely close to his only sister, and which very publicly consummated the sullying of Lyanna’s honor.

It is interesting to consider the mindset of Brandon in this moment. He was no stranger to romantic interests from men to women, even among highborns: his affair with Barbrey Ryswell was proof enough of that, and even at the tourney itself Brandon was rumored to have attracted the attention of the beautiful Ashara Dayne (whether the Dornish lady was actually attracted to Brandon or his quiet younger brother is lost to history). Yet when Rhaegar offered Lyanna the crown, Brandon rightly saw the insult the crown prince offered to his family. Brandon and his father had worked hard to ensure that the next generation of Starks would earn the respect of southron Westeros, and Lyanna – future Lady of Storm’s End – was key to that respect. If Lyanna accepted the prince’s offer to become his mistress, the most she could hope for would be a brief reign at court, with perhaps a bastard child, before Rhaegar’s affections turned to another; then, her virtue tattered, she would return to Winterfell with no greater marital prospects than one of her father’s household knights. The evolving southron ambitions power bloc would be shattered, and Brandon – for all his indulgence in sexual affairs and possible (though unacknowledged) bastards – could not risk all the southron training which had led to his current position and the careful plans for his house’s future.

It was another chivalric moment which defined the last years of Brandon’s life – and this, like the crowning of Lyanna as queen at Harrenhal, would have far-reaching repercussions. Sometime between his betrothal and his fatal journey to the capital, Brandon made a fateful trip to Riverrun and his betrothed. Hoster Tully’s ward had challenged Brandon for Catelyn’s hand, and Brandon would not fail to respond:

They met in the lower bailey of Riverrun. When Brandon saw that Petyr wore only helm and breastplate and mail, he took off most of his armor. Petyr had begged her for a favor he might wear, but she had turned him away. Her lord father promised her to Brandon Stark, and so it was to him that she gave her token, a pale blue handscarf she had embroidered with the leaping trout of Riverrun. As she pressed it into his hand, she pleaded with him. “He is only a foolish boy, but I have loved him like a brother. It would grieve me to see him die.” And her betrothed looked at her with the cool grey eyes of a Stark and promised to spare the boy who loved her. (“Catelyn VII”, A Game of Thrones)

Brandon demonstrated considerable restraint here, more than might have been expected for a famously hot-headed man. Certainly, Brandon – or, for that matter, any high-ranking nobleman – might have seen a fair amount of insolence in young Petyr Baelish’s challenge to wed Catelyn himself: Brandon was the heir to Winterfell, but Petyr was only a minor lord’s son, heir to a mere strip of rocky Vale seashore. Nevertheless, Brandon’s training in chivalry would not allow him to indulge the fury he might have felt at such a minor lordling trying to wed his betrothed. Not only would Brandon match his opponent’s decision to wear light armor, but he listened to his lady’s pleas for mercy, granting her this boon as a stern, just lord never could on his own. Indeed, Brandon was a consummate and dedicated follower of chivalry even in this moment, as he employed Catelyn’s young brother Edmure as his squire for the duel; even in such a tense moment, Brandon underlined his adherence to the southron ambitions power bloc.

Of course, practically speaking Brandon could afford such chivalry. Daemon Blackfyre might have perished from his determined adherence to knightly virtue, but Petyr posed a much lesser threat to the well-trained heir to the North. Still, Brandon was not altogether forgetful of knightly conduct in the fight:

That fight was over almost as soon as it began. Brandon was a man grown, and he drove Littlefinger all the way across the bailey and down the water stair, raining steel on him with every step, until the boy was staggering and bleeding from a dozen wounds. “Yield!” he called, more than once, but Petyr would only shake his head and fight on, grimly. When the river was lapping at their ankles, Brandon finally ended it, with a brutal backhand cut that bit through Petyr’s rings and leather into the soft flesh below the ribs, so deep that Catelyn was certain that the wound was mortal. He looked at her as he fell and murmured “Cat” as the bright blood came flowing out between his mailed fingers. (“Catelyn VII”, A Game of Thrones)

The counterfactual analysis of what might have had happened had Brandon actually killed young Littlefinger in that moment is too elaborate to expound upon here. What is important to note is that Brandon strove to maintain the chivalric appearance in the duel: he would continually call upon Petyr to yield until it was clear Petyr would fight on until he died. Perhaps this was a matter of appearance: in front of his Tully fiancee and the heir to Riverrun (and, one might suppose, Lord Hoster as well), Brandon may have wanted to appear the ideal southron knight, defending his lady’s honor while simultaneously gallantly offering his opponent a chance to surrender nobly.

Indeed, whether or not he intended to do so, Brandon’s appearance of gallantry would leave an impression on his intended father-in-law.

“He was on his way to Riverrun when . . .” Strange, how telling it still made her throat grow tight, after all these years. “. . . when he heard about Lyanna, and went to King’s Landing instead. It was a rash thing to do.” She remembered how her own father had raged when the news had been brought to Riverrun. The gallant fool, was what he called Brandon. (“Catelyn VII”, A Clash of Kings)

Around a year after Harrenhal, Brandon made his way south, to wed his bride at Riverrun. Upon learning that the crown prince had absconded with his sister, however, Brandon’s wolfsblood rose up again. He might have been able to put on a good chivalric front for Catelyn and Hoster, but the crown prince had breached all reasonable conventions by his action. Such action required vengeful retaliation – not the measured challenge of the southron knight, but the full fury of the wolf.

Come Out and Die

Brandon had not told his soon-to-be goodfather Hoster of his plans, and one might suppose he did not inform his own father either. Both men would have understood the misconduct of the crown prince, of course – in their minds, he was no better than the outlaw Kingswood Brotherhood, which had kidnapped Lady Jeyne Swann not so long before – but both also knew the value of taking time with careful planning: the North-Vale-Riverlands-Stormlands power bloc had not been built in a day. Brandon, however, was aggrieved, and as Lady Barbrey had noted years before, had never been shy about taking what he wanted – or bearing his fangs.

Still, there was at least some measure of thought in Brandon’s actions, even if that measure was decidedly small. Brandon would not go alone to the capital: he took with him his companions, the southron friends he had made in the Vale and Riverlands, as well as his squire Ethan. This was a show of strength: Brandon might have been a vengeful brother, and his appeal one of Stark honor, but bringing his companions demonstrated that there was a real political threat behind Brandon’s admittedly raging words. Brandon was the heir to the North, Elbert the heir to the Vale, Jeffory and Kyle scions of powerful vassal houses: the potential power bloc against the crown if the Starks were refused justice was considerable.

Upon arriving in King’s Landing, however, Brandon’s fury got the better of his sense:

Jaime poured the last half cup of wine. “He rode into the Red Keep with a few companions, shouting for Prince Rhaegar to come out and die. But Rhaegar wasn’t there. Aerys sent his guards to arrest them all for plotting his son’s murder … ” (“Catelyn VII”, A Clash of Kings)

To be sure, plotting the murder of a king (or his consort of heir) was a treasonous act in our own world, as well as in Westeros; it had been the treasonous talk of Barba Bracken and her father, speaking of how she would become queen once Naerys died, which had driven Aemon and Daeron (and their faction at court) to call for the royal mistress’ refusal. Nor was it wise of Brandon to frame his challenge of a duel (and certainly, having upheld his own lady’s honor in a duel, he would have envisioned a similar scenario with the crown prince) in such bloodthirsty language. Nevertheless, nothing of Brandon’s conduct suggests that he had conspired beforehand to murder Rhaegar; northmen are no strangers to cold and bloody vengeance, but Brandon had been trained in southron ways, and had reason to know that a lord’s heir who murdered the crown prince would face drastic political repercussions, no matter how justified his conduct in his own mind. Five lordlings and a squire hardly made a powerful enough force to storm the Red Keep and murder Rhaegar in his bed, but they were from respectable enough families to witness his grievance and back up Brandon’s call to arms.

The Mad King – that gaunt, suspicious figure whom Brandon had last seen presiding over the Tourney of Harrenhal – had no patience for treason, neither from his much-distrusted own son nor from unruly vassals. Brandon, in his hot-bloodedness, had demanded Rhaegar’s head, and such a demand (however insulted House Stark might have been, and however much Aerys personally disliked Rhaegar) was a threat to the crown that paranoid Aerys could not ignore. Arresting Brandon and his companions, Aerys called for the fathers of the boys – including Rickard himself – to come to King’s Landing. There, Brandon’s friends and their fathers (save Ronnel Arryn, who had died when Elbert was only an infant) suffered a gruesome end:

“Aerys accused them of treason and summoned their fathers to court to answer the charge, with the sons as hostages. When they came, he had them murdered without trial. Fathers and sons both.” (“Catelyn VII”, A Clash of Kings)

Brandon had certainly not expected this horrific fate to befall his companions. Even if he himself had called for the death of the prince, they had done nothing more than stand by his side and witness his fury. The king might have spared young Ethan (the Mad King was no stranger to mocking customs and chivalry) but the proud sons of the Vale and Riverlands – including the heir to the Eyrie – were murdered on the whim of the monarch. It may be imagined Brandon regretted, if not his actions themselves, then the fates of his friends: he had tried to be the heroic coalition leader, riding for justice, but had instead dragged noble companions to death at the hands of a madman.

Worse was to befall the wolves themselves. Rickard, having traveled to the capital in accordance with the king’s wishes, had been seized and arrested himself. The Lord of Winterfell then requested a trial by combat, to which Aerys agreed, but with a sinister twist: dragons being fire made flesh, the champion of House Targaryen was rightly fire, and Rickard would burn in his armor. Brandon would not be left to the side, however: he had a front-row, fatal seat to his father’s “trial”:

“When the fire was blazing, Brandon was brought in. His hands were chained behind his back, and around his neck was a wet leathern cord attached to a device the king had brought from Tyrosh. His legs were left free, though, and his longsword was set down just beyond his reach.

“The pyromancers roasted Lord Rickard slowly, banking and fanning that fire carefully to get a nice even heat. His cloak caught first, and then his surcoat, and soon he wore nothing but metal and ashes. Next he would start to cook, Aerys promised . . . unless his son could free him. Brandon tried, but the more he struggled, the tighter the cord constricted around his throat. In the end he strangled himself.” (“Catelyn VII”, A Clash of Kings)

SomethingLikeaLawyer has spoken to the mockery of justice which Aerys’ double execution of the Starks displayed, but the point bears repeating for Brandon. Brandon, like his father, had the right to a trial by combat to prove his own innocence, but he was not even given the dignity, however perverse, of “fighting” the crown’s champion. His execution was designed to torture, mentally and physically. Not only was Brandon forced to watch his father suffer most grievously, but Brandon would be tricked with a chance to rescue him. For a man like Brandon, a trained and ready swordfighter, the cruel taunting of the out-of-reach sword must have been infuriating; Aerys likely knew how ferociously Brandon could fight (given that the Mad King likely witnessed Brandon’s martial display at the Tourney of Harrenhal), and taunted him with the prize of his salvation just outside his grasp. For a man who always sought to take action, against a prince who had twice over sullied his sister’s honor, the ability to save his father always held just outside his grasp would have been agonizing. That which Brandon had come to challenge Prince Rhaegar on – the honor of the Stark name – he had to watch literally go up in flames: Aerys was demonstrating, to Brandon and to his court, that the nobility of the wolves of Winterfell was meaningless, able to be removed, with extreme cruelty, at his pleasure.

Conclusion

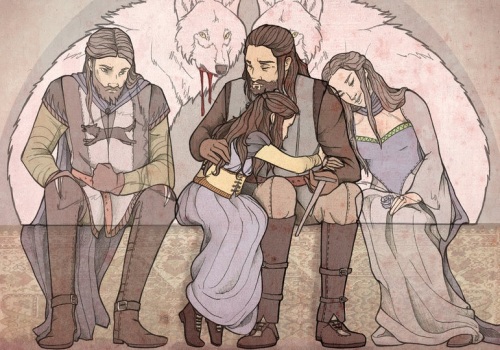

Brandon, Arya, Ned, and Lyanna (image credit to mustamirri)

“The Others take your honor!” Robert swore. “What did any Targaryen ever know of honor? Go down into your crypt and ask Lyanna about the dragon’s honor!” (“Eddard II”, A Game of Thrones)

It may be, as Robert said, that Rhaegar never knew anything of honor. The same, however, could not be said of Brandon. He had been too long trained in southron customs not to develop a sense of chivalry – to respond to a challenge to his lady’s hand in perfectly knightly fashion, or to recognize the chivalric insult that was Rhaegar’s crowning of Lyanna at the tourney of Harrenhal. Brandon was certainly not the fairy-tale ideal of a knight – his supreme self-confidence in taking the women he wanted, no matter how highborn, was not a heroic trait (although a common enough one among lords) – but he was a man who, in different circumstances, would have become a more southron Lord of Winterfell than any of his predecessors.

As southron as he became, however, Brandon was still a wolf, and centuries of Northern instinct could not be wiped out in a generation. The insult to Lyanna might have come in a chivalric context, but Brandon’s response displayed the Northern fury and spirit of vengeance more akin to the Hungry Wolf than to southron customs. His honor was a wolf’s honor – southron in its principle but Northern in its fury – and it was that volatile mix of influences which led Brandon to his death. The grand plans for the future, of a strong pan-Westerosi power bloc, had literally gone up in smoke, swallowing pawn and player both.

Thanks for reading! Questions? Comments? Find me on Twitter, and follow the blog while you’re there! Remember you can also find the blog on Facebook and Tumblr as well!

I think it’s a bit harsh to blame him for, in his mindset, defending his sister.

Most people would do the same in his situation. The insult at Harrenhal could be forgiven, but backing it up by abducting Lyanna gave him no choice but vengeance.

I think many other monarchs would have at least freed Lyanna and punished Rhaegar for this foolishnes (wich in the end was the spark that brought his dynastys downfall).

I think the blame here, as in many other situations, should go to Rhaegar and Aerys, one for his foolishnes, the other for his paranoia and cruelty.

Greetings

Entering the red keep shouting for rhaegars head was very recless and kind of dum, didint he know that was reason or that aerys was crazy?, he is not stupid, he should had tried a more diplomatic way, but i understand your point.

Thing is, that this approach to the problem was, at least i think so, fully understandable in the culture of Westeros and especcialy the north.

A king (or prince) who is like Rhaegar is a danger for the whole continent, if you look from Brandons perspective and think he abducted her.

A more diplomatic approach would indeed be more wise, but i think even if someone pointed out that Rhaegar was wrong and demanded some punishment for him, Aerys would do the same as he did.

Greetings

Greetings

Why Rhaegar had to disappear with her? I understand that he had caused a lot of damage already, by taking away a noblewoman who was engaded to someone else. But it would be far less worse than the idea that he abducted and raped her.

Why he didn’t tell anyone else? No one in court? Why he didn’t send someone before the battle of the trident to warn Eddard Stark that his sister was fine, that she had gone with him by her own free will. “Ow, but he wouldn’t believe!” Why not ask someone who Eddard trusted to see Lyanna and check if Rhaegar was saying the truth?

Good essay, but i dont really agree with it, Brandon doesn t seem particularly southern in its atitudes, i dont think he was a knight, he was faith of the old gods and although not without some cases this is not very common, and he didnt need to be a knight to joust specially being the heir to winterfell, i dont think anyone would prevent him from jousting if he wanted, is it a southern tradition to make aliances and play politics?, sure richard and brandon where making southern aliances but that act is not southern, northerners do those things not in such a grand scale but they do those things as much as in the south, in the dual with petyr again he doesnt seem especialy chivalrous, catelyn and edmure were apart of that culture so he played the part, i think the counter argument is on point here, he was restrained ?, maybe a bit again with cat there i dont think he thought it was a good idea to go full berserk there, but he almost killed petyr cat had to beg for him not to do it, i think you are right that he felt ofended that this almost baseborn kid was chalenging him and he gave him a good lesson and scar to remind him not to mess with his betters, he slept with barbrey ryswell not caring about her honer or reputation made no move to marry her, and he seemed like a person who liked his womem and to party a lot, all things that are not very chivalrous or knightly in his defense this is commom practice, and his hot temper and rush actions are very much in line with the wolf blood northern thing, in conclusion i think he was a «true» northerner but i do think he had a lot of insight into southern culture, he had to havind so much contact with it , but he was very proud of is roots and chose not to be very influenced by the southern ways, but this is my opinion.

Just as i side note for what we know of him i dont like brandon, i dont think he was a bad person, but he seems very hot tempered was a womanizer and to me seems to have this kind of bully atitude that i dont like.

Great work Nina,thanks a bunch.I’m a great fan of Song of Ice and Fire and I appreciate any work on the subject.With a lot of time for listening and a bit of time for reading this is great for me.Also every article is more interesting with your introduction comments!So,if you keep recording,we’ll keep listening.All the best in 2016!

Wow,amazing article. I kinda always figured him as the bro dude that got himself killed,but in reality could have been the twin of Robert baratheon,winning allies and coyrteous,yet wroth in anger.

The comparison to Ned stark seems vastly different.

A very interesting read! Glad to read you portraying Brandon as someone having more to him than the rash, impetuous, reckless man many think of him as… the chivalric, Southron side of him is very well brought-out

Great read. Although, I don’t think the Power Bloc was destroyed by Brandon, in fact, it appears to me that his death cemented it. Without the honor of the houses that fell with Brandon, would Robert and Ned have had the outright devotion of those houses in order to win Robert’s Rebellion?

I’ve was reading through the World of Ice and Fire to learn more about the Stark history. I can’t find reference to the long secession crisis after Cregan the One Day Hand. Where does this information come from? It seems like we have much more Lannister history in the World Book than the Starks, unless I’m missing something. Is part of the Stark history found somewhere besides the section on the North, or are there other source information that I am not aware of?

Another great one – it always amazes me that you’re able to divine so much plausible, devoid-of-tinfoil backstory from the small amount of actual text we’re given – and above all – thanks again for narrating it – your style is sublime. More more more!

Really great work, thanks for turning this into a podcast!

a good essay, and I think you do pick up the role Rickard had planned for him in the SA block from the hints in Martin’s texts; especially the group that he assembled to go to King’s Landing, as we know Martin does not randomize details of that sort. A hand like Tywin, or even honest counsel, would have recognized the gesture politics of the “power bloc” as you dub it. Its also interesting to compare the make up of that bloc with the strike team Ned takes with him to the Tower of Joy, and how the composition of each group is astutely selected based on the nature of the mission and what the Stark leading each expected to encounter there.

I disagree on one point, though; Brandon, as the next Stark in Winterfell, was not the son made to fit into the southern mold, although he his far from a generic northerner. Rather it is Eddard, as the second son, and the one who could be married away from Winterfell who was raised to fit in with (and perhaps live in) the southern courts and their traditions, and I believe there is a good deal of textual evidence for this. Ned, of course, has to become the Stark in Winterfell, and happily embraces the role of true Northman, but he fit in and understood the lands south of the Trident better than his brother (but that is another meta)