The Princess and the Queen Book Cover (image by nateblunt)

Introduction

In “The Rogue Prince”, Archmaester Gyldayn explores the surface peace and hidden turbulence of the reign of Viserys I Targaryen, immediately preceding the Dance of the Dragons. Though the novella is written in a more “non-fiction” style than the main novels, Gyldayn’s work nevertheless features undercurrents of drama and intrigue. Nowhere is this more apparent than in two mysterious (and quickly successive) deaths recorded to have occurred in 120 AC. The first victim, Laenor Velaryon, was the heir to Driftmark and husband of Princess Rhaenyra, her future consort when (or if) she came into her throne. Not long after his death, tragedy would strike House Strong with the loss of both its lord, Lyonel, and his heir, Ser Harwin.

In both cases, Gyldayn notes from his primary sources a number of suggested suspects, without settling on one likely culprit. It becomes the duty of the reader, then, to examine the evidence and determine which, if any, of the suspects offered seem likely to have arranged these murders (if, indeed, both were even premeditated crimes at all). Investigating the charged atmosphere of Viserys’ court, and the factions playing for power, new suspects appear – those who stood to gain much from these men’s deaths, and who helped contribute, if unknowingly, to the bitter and bloody struggle on the death of the king.

Consort of a Princess, Killed by a Lover: Laenor Velaryon

Laenor Velaryon was not the first victim of what Gyldayn would call “the Year of the Red Spring”; his elder sister Laena, wife of Prince Daemon Targaryen, died in the first month of the year. Laena’s death, however, was natural, if nonetheless tragic- a failed attempt to give Daemon a son. Ser Laenor, by contrast, had been publicly murdered at a fair in Driftmark. The culprit is known, dozens of witnesses saw Ser Qarl Correy stab Laenor after an argument turned violent. However, Gyldayn hints at something deeper, a conspiracy that turned this crime of passion into a cold-blooded, methodical killing. Who, however, had the motive to fatally stab the heir to Driftmark?

First, one must consider Ser Laenor himself. Laenor was the only son of Lord Corlys Velaryon – seafarer, adventurer, and extremely wealthy Lord of the Tides – by his wife, the Princess Rhaenys – the so-called “Queen Who Never Was”, who had been passed over by Jaehaerys I in the succession in 92 AC. Laenor himself, as a boy of seven, had been a claimant himself for the throne, when his great-grandfather called a Great Council on the death of his chosen heir, Baelon. Like his mother, however, Laenor was not destined to sit the Iron Throne, the lords of the realm preferred his male-line cousin, Viserys, instead.

Still, Laenor was the blood of the dragon on both sides of his lineage; with his wealthy and ambitious Velaryon father, his dynastically powerful Targaryen mother, and his own Valyrian appearance and dragonriding ability, Laenor posed a potential threat to the line of King Viserys. Accordingly, Viserys betrothed his daughter Rhaenyra – his only child by his first wife, and his declared heiress – to Laenor, binding the lines in dispute at Harrenhal back together and (hopefully) avoiding war. At the age of 20, the newly knighted Ser Laenor wed the Princess Rhaenyra; all was set for Laenor to accede as consort on the death of his goodfather.

All was not well in the marital life of the royal couple, however. Even before his marriage, Laenor had been noted for a distinct lack of interest in women, and after the wedding, Laenor spent much time apart from his wife. Rhaenyra’s firstborn, a son with brown hair and eyes – utterly unlike the Valyrian-looking Laenor or Rhaenyra – seemed to confirm what some at court suspected: Rhaenyra had taken a lover, and the child was a bastard. Two more sons, each with the same “common” features, followed.

Then, in 120 AC – three years after the birth of the youngest of these sons – Laenor was murdered. The circumstances of his death were corroborated by a number of eyewitnesses (with more detail than was noted in the writings of then-Grand Maester Mellos). Laenor had been attending a fair in Spicetown, on his island home of Driftmark, when he began quarrelling with a household knight, Ser Qarl Correy. Blades were drawn, Laenor was killed, and Correy fled the fair, never to be seen again.

Who was Qarl Correy to the presumptive prince consort? Correy was a household knight, but appeared to share a more personal relationship than might be expected of a simple retainer. As noted above, Laenor preferred the company of handsome squires his own age, and at the wedding tourney he had laughingly given his own garter to his favorite knight, Joffrey Lonmouth, after Rhaenyra bestowed hers on Harwin Strong. Qarl and Laenor were thereafter rumored to have become lovers (after Ser Joffrey’s untimely death at the hands of Criston Cole during the wedding melee), and Ser Qarl was certainly a friend and companion to the heir to the Velaryon fortune.

So was Laenor’s death a lover’s quarrel, bloodily escalated? Septon Eustace certainly believed so. In his account of the incident, the court septon indicated that personal, rather that political, motives drove Correy: Ser Laenor was rumored to have grown cool toward the knight, and had a new favorite in a young squire, much to Qarl’s jealousy. Crimes of passion are nothing new, either in our own world or in Westeros; one need only look to the brutal suffocation of Shae by Tyrion to see how strong feelings of emotional betrayal can lead to murderous results. Security around Laenor may well have been low: Spicetown was a prominent town on his own home island and future inheritance, the realm was at peace, and Laenor himself had made no known political enemies. Qarl, as both a household knight and Laenor’s companion, would have had close access to him; as Laenor’s presumed lover, Correy may also not have been watched closely, giving him enough time to draw his blade against his friend before forces in Spicetown and around Driftmark could retaliate.

Still, some details undercut Qarl’s sole participation in the murder. The witnesses to the murder noted that Qarl cut down several men who tried to stop him in his flight from the scene of the crime. Qarl, however, still faced an escape problem: Driftmark was the seat of House Velaryon, and with the heir to the house having just been murdered, Velaryon retainers would have immediately begun tailing Correy to bring him to justice. Correy was only a household knight, with “a peasant’s purse”, as Mushroom named it, despite his “lord’s taste”; he himself would not have had sufficient money to bribe a ship’s captain to transport him away from the island, especially if he were being pursued by Velaryon forces. The knight would have needed a third party, someone who could have paid for his safe and discreet passage from the scene of the crime. Nor is Septon Eustace always an unbiased source: the septon was a vehement Aegon supporter during the Dance, and is thought to have invented Aegon’s initial reluctance to take the throne in order to paint his chosen king in a better historical light.

Mushroom, the court fool, offered a different option. According to Mushroom, Qarl Correy killed Laenor not out of simple jealousy but on the orders of Prince Daemon Targaryen, brother of the king. Anxious to rid Rhaenyra of her husband, Daemon paid Correy to dispose of Laenor, arranged passage for him out of Driftmark – then had his throat slit and his body dumped into Blackwater Bay.

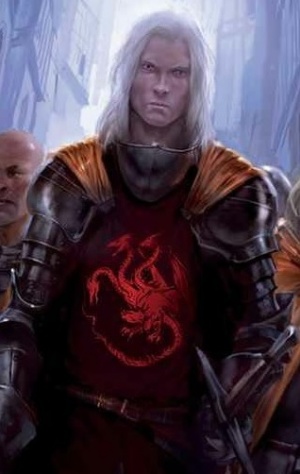

Daemon Targaryen (image by Marc Simonetti)

Daemon certainly had the means to enact such a scheme. As the king’s brother, Daemon would not have lacked for more than sufficient funds (presumably aided by the rich dowry Lord Corlys may have provided on the marriage of his only daughter) to arrange the incident. The circumstances of this scenario in particular recall the death of Dontos Hollard: having been promised a large payment by Littlefinger to smuggle Sansa out of the Red Keep in the chaos following the poisoning of Joffrey (a poisoning Littlefinger helped orchestrate), Dontos delivered the Stark heiress to Baelish – and received three crossbow bolts in the head and chest before his body was torched to prevent discovery. Without Correy himself to reveal the plot, there would be little opportunity to discover that Daemon was the prime conspirator; he may have enjoyed a dark reputation, but Daemon remained a royal prince, and any accuser would need firm evidence (or a very powerful backer) to name him a murderer. Finally, Daemon’s time as captain of the gold cloaks of King’s Landing had made him familiar with the thieves and cutpurses in the slums of Flea Bottom; the prince’s willingness to deal with the less scrupulous members of society (and knowledge of how they operated) may have served equally well in arranging the murder on Driftmark.

Did Daemon have sufficient motivation? Mushroom suggested that the cause was Daemon’s desire to make Rhaenyra a widow, and thus marry her himself. The two had been rumored to enjoy some degree of physical relationship; Mushroom asserted that Daemon asked his brother for his daughter’s hand after revealing the extent of her “training” – teaching the princess how to seduce Ser Criston Cole – while Septon Eustace insisted Daemon actually took Rhaenyra’s maidenhood. Nor had Daemon been averse to making marital arrangements to further his own ambitions: after being freed of Rhea Royce, Daemon asked for the hand of Laena Velaryon – not merely out of love, but as a means to ally with the powerful House Velaryon after being roundly excluded from the succession. A match with Rhaenyra, however, would be an even grander coup: now he, and not Laenor, would be the prince consort, and if he were not king in his own right, it would be the nearest Daemon would get to his long-desired throne.

Still, his gains were not assured, and his involvement in the plot made his position precarious. Even if Rhaenyra were widowed, she had no guarantee of marrying her uncle; the hand of the heiress to the Iron Throne had been dangled as a prize for many lords throughout the realm, and though Rhaenyra was not the beauty she had been, her remarriage would bring significant political advantage. In addition, even if they wed, her three sons from her Velaryon marriage would come before any sons Daemon had with her. If Daemon desired Rhaenyra personally, he might have taken her as a lover while keeping Laenor alive; the princess had already shown herself amenable to taking a lover, and any resulting children would be easy to claim as Laenor’s, given the prince and princess’ shared Valyrian features (and, as a bonus for Rhaenyra, undermine the argument that the elder Velaryons were bastards as well; in a family of mixed Valyrian/non-Valyrian features, the case for illegitimacy for a few would become weaker). Moreover, Daemon’s political strength came largely from his alliance with House Velaryon, the only party strong enough to stand against both the blacks and the greens. Should Lord Corlys and Princess Rhaenys discover that their own son-in-law had arranged their only son’s murder, however, that support would disappear instantly, and Daemon would find himself a political pariah (if not executed quickly thereafter). Finally, Mushroom is not an unbiased source either: a court dwarf with a gossipy style and a taste for the lurid, Mushroom may have retroactively named Daemon as the culprit to capitalize on the latter’s scandalous marriage to Rhaenyra not long after Laenor’s death.

One suspect – or, rather faction of suspects – is, however, not mentioned by any source, yet should not be discounted. The greens, led by the former Hand Ser Otto Hightower and his daughter Queen Alicent, worked hard to promote the interests of Alicent’s eldest son, Aegon. The queen and her father would have known that a succession crisis would break out on the death of the king; Viserys had never rescinded his declaration that Rhaenyra would be his heiress, and while Aegon was his eldest son, certain powerful lords would surely call for Rhaenyra to be crowned queen. Alicent and Otto would have also recognized the great power of the black power bloc as it stood at the time of Laenor’s death. The Velaryons were never wealthier or more powerful than they were in the time of Corlys: their fortune was on par with the Lannisters or Alicent and Otto’s own Hightowers, and the merging of two Targaryen lines with the marriage of Laenor and Rhaenyra created very politically potent heirs in the three sons of that union. The Velaryon-backed blacks also controlled more dragons, and more experienced dragons, than the greens: Rhaenys had been riding Meleys for longer than any other dragonrider, Daemon’s Caraxes was a battle-hardened beast, Rhaenyra’s Syrax and Laenor’s Seasmoke were imposing dragons in their own right, and all three of Rhaenyra and Laenor’s sons had growing dragons of their own (and Laena, until her death in 120 AC, controlled the mighty Vhagar). Should war come, the greens – with just Aegon’s Sunfyre, Helaena’s Dreamfyre, and Daeron’s Tessarion – would find themselves at a naval and draconic disadvantage.

Alicent had tried to remedy this situation once before. When Rhaenyra was 16 and her betrothal was being debated, Alicent had suggested wedding her to Aegon when the prince came of age. Viserys, however, refused to indulge the Hightower ambitions, especially when the prince and princess so openly disliked one another (and when Rhaenyra herself would have had to wait at least 7 years before she would be able to have heirs of her own). Rhaenyra was summarily wed to Laenor, and Alicent deprived of a means to bind together the competing claims of Viserys’ children.

By 120 AC, however, the future Aegon II was 12 going on 13, old enough by Westerosi standards to consummate a marriage. If Rhaenyra could be rid of her Velaryon husband, unmarried and unbetrothed near-adult Aegon would certainly be a choice, if not the king’s first choice, for her new spouse; additionally, with three Velaryon heirs, Viserys might not be so openly concerned about the ambitions of the Hightowers. Of course, Alicent and the greens also believed these Velaryon boys to be bastards; if this were proven, the three princelings could be nearly wiped off the succession, leaving the path open for the children of Rhaenyra and Aegon to inherit. The Velaryons would surrender their powerful role as first among the Targaryens’ vassals, and the Hightowers, as ancestors to the successive dragonkings, would shine even brighter.

Naturally, Alicent and the greens would need a way to arrange the murder. Alicent was not above installing or arranging for informers to suit her own ambitions: when Viserys himself died in 129 AC, Alicent was told by a servant she had specifically ensured would inform her and no one else of the king’s passing. Nor would she and the greens have failed to recognize the importance of keeping informers on Rhaenyra, especially as concerned her married life: if the greens were truly eager to unseat Jacaerys, Lucerys, and Joffrey as the next royal heirs, they would do worse than to gather as much information about their supposed bastardy as possible, and Laenor’s marked distance from his wife would have aided their case. Laenor himself was likely not discreet about his close feelings toward Ser Qarl: it was at his own wedding celebrations, after all, that Laenor had bestowed his garter on his close friend (and possible lover), Ser Joffrey Lonmouth.

So Alicent and the greens, receiving information on the presumptive prince consort’s extramarital dalliances, might have noted the prominence of Qarl Correy. If the greens were watching Correy – either as merely Laenor’s lover or an informant in his own right – they might have noted his financial instability and growing frustration and desperation as Laenor looked to replacing him with another threat. Playing on these two stresses, Alicent and her green faction might have bribed Ser Qarl to murder Laenor, assuring him that he would be well-paid (from the wealthy Hightower purse) and able to escape Westeros. As further assurance, Alicent and the greens might have encouraged speculation that Daemon himself was the conspirator, further undermining the powerful alliance between Rhaenyra and Daemon and the Velaryons (and keeping the green faction’s hands clean, when King Viserys looked to give Rhaenyra a second husband). This green involvement may also explain why the vehemently pro-green Septon Eustace named Qarl as the sole killer: by framing the murder as a mere crime of passion between lovers, Eustace would divert attention from his royal champion (and, by emphasizing Laenor’s affair with Qarl – and his related inability to have fathered Rhaenyra’s sons – Eustace’s account could help undermine Rhaenyra’s cause).

In the end, either Daemon or the green party seem likely as culprits for arranging the murder of Laenor Velaryon. Both had roughly the same means and opportunity to do so: both Daemon and the Hightower-back greens were wealthy, and both would be familiar with using informers to further their own ambitions. The motive for either suspect was the same: to rid Rhaenyra of her husband and seize her claim (through marriage) for each side’s respective ambitions. Only the likely murdered Qarl Correy might have known the whole truth; if he did, the secret was lost with him under the waves of Blackwater Bay.

Lover of the Dragon, Consumed by Fire: Lyonel and Harwin Strong

Ser Laenor Velaryon, however, was not the only body the Year of the Red Spring would claim. Not long after Ser Laenor’s funeral (and the loss of the smallest victim of that bloody year, Prince Aemond’s eye), two more important members of King Viserys’ court would perish: Lord Lyonel Strong, Hand of the King and master of Harrenhal, and his elder son and heir, Ser Harwin, known, for his famous strength, as Breakbones. The two men, returning to their family seat, were killed in a fire which also claimed a number of servants and Strong retainers. A chance accident, perhaps, another example of the supposed curse on Harren’s folly – or maybe something more.

Once again, Lord Lyonel and Ser Harwin merit some personal consideration in order to understand the mystery of their deaths. Lord Lyonel Strong, the first of his family to rule Harrenhal, had enjoyed at least a decade and a half-long career at court at the time of his death; having been named master of laws in 105 AC, Lyonel secured a greater prize in being named Hand in 109 AC. As Hand, Lyonel ousted the long-serving Otto Hightower, who had earned the king’s displeasure by regularly questioning the right of Rhaenyra to succeed over his Targaryen grandsons.

Typically for an ambitious courtier and eventual Hand, Lyonel worked to gain his children court placements. His two daughters became handmaidens to Princess Rhaenyra – a boon for noblemen both real-world and Westerosi – while his heir Harwin became a captain in the gold cloaks, at a time when Daemon Targaryen was the City Watch’s commander. The younger of Lyonel’s sons, Larys the Clubfoot, joined the king’s confessors.

It was Ser Harwin, however, who would become infamous in the story of Rhaenyra and the court of Viserys I. How much Breakbones interacted with the royal family is unknown (Harwin may have been that ambitious captain who reported Daemon’s crude remark on the deaths of Viserys’ first wife and newborn son), but he certainly noticed the beautiful Princess Rhaenyra. He was considered of sufficient breeding to pay court to her when the eager sons of the realm’s best families vied for her hand (though he, like the rest, was passed over for Laenor Velaryon). Before the princess’ marriage, however, rumors emerged that Rhaenyra, rejected by Criston Cole, had taken Ser Harwin as her lover – rumors not dispelled when, at the marriage tourney, Rhaenyra publicly bestowed her garter on her new champion and sworn shield. Thereafter, Harwin became the “foremost of the blacks”, in Gyldayn’s words, always at Rhaenyra’s side (even at the birth of at least one of her sons). Though the appearance of Ser Harwin remains unknown, it was an article of faith among the green faction that the true father of Rhaenyra’s Velaryon-surnamed sons was none other than Ser Harwin Strong (certainly, the very existence of green suspicion lends credence to the idea that Harwin shared the features of the young Velaryons, at least in part).

Gyldayn, typically, names no one culprit, but presents a multitude of possible suspects. It may indeed have been simple ill chance that Harwin and Lyonel died. A candle or torch, left carelessly burning next to flammable material, could set the men’s rooms ablaze, and while such a fire would never be able to consume all of the gargantuan Harrenhal, the very size of the castle may have worked against quick efforts to put out the fire until it had claimed its unfortunate victims. Black Harren’s curse might have claimed another victim, Lyonel and Harwin simply being the next in a line of men and families who met untimely ends in the great Hoare castle. Still, with the air of suspicion and intrigue which pervaded Viserys’ court, especially as his reign entered its last phase, the deaths of the Hand and his infamous heir seem unlikely to ascribe to simple bad luck or evil.

As a court observer (if occasionally a less than credible one), the fool Mushroom offered his own suspect: Corlys Velaryon.

Corlys Velaryon (image by Enife)

According to the dwarf, Corlys arranged for the fire to kill Harwin, as an act of revenge against the man who had cuckolded his son Laenor. Mushroom, however, thrived on exaggeration; his Testimony of Mushroom is an explicit, debauched chronicle of life at Viserys’ court. Moreover, Corlys had no court position, instead preferring his island seat, and whatever rumors targeted him as the culprit would have come to Mushroom second- or even third-hand, undermining their credibility. Lord Corlys would have needed a man on the inside at Harrenhal to arrange the fire – not the most natural alliance for a lord whose seat lay relatively far from the half-ruined castle. Likewise, Corlys was not a man known for a desire for vengeance: though ambitious for his family and House, Corlys was a shrewd statesman, aware that the black party and his nominally Velaryon grandsons would lose much in eliminating the powerful and wealthy Lord of Harrenhal and his ardently pro-black heir. If Harwin’s supposed affair with Rhaenyra had made Corlys wroth, the Sea Snake might have taken any opportunity in the six years between the birth of Prince Jacaerys and the fire at Harrenhal to “remove” Harwin. As with the First Blackfyre Rebellion, the length of time between the supposed triggering wrong and the reaction undermines an emotional catalyst.

Septon Eustace suggested Daemon Targaryen as the true culprit, though again with an emotional motivation. According to the court septon, Daemon wanted to remove a rival for Princess Rhaenyra’s affections, so that he himself could marry Viserys’ declared heiress. Daemon was known – more so than Corlys, certainly – for acts of murderous retaliation, even arranging for the murder of one of Aegon II’s sons after the death of Lucerys Velaryon. Daemon would still have needed to arrange for a contact within Harrenhal or the Strongs’ party to facilitate the conspiracy – perhaps relatively easy for a prince who had made unscrupulous friends throughout King’s Landing during his tenure with the gold cloaks, but certainly not a natural connection for Daemon. Yet to describe the motive in terms of Rhaenyra’s affection seems to misread Prince Daemon’s character. Daemon never lacked for self-confidence, nor for the love of his niece. With Harwin separated from the princess on Viserys’ orders and forced to return to Harrenhal, Rhaenyra would have little opportunity to visit the rumored father of her sons, and much less to wed him herself. Daemon was physically closer (having lived with his wife, prior to Laena’s death, on her home of Driftmark), dashing and dangerous; he had no reason to believe that he could not woo and win his niece himself, whether or not her former paramour still remained alive in the Riverlands.

Not only the king’s brother but the king himself was accused of foul play. According to Grand Maester Mellos, King Viserys ordered the murder of Ser Harwin to ensure Breakbones could never reveal the secret of Rhaenyra’s sons’ true parentage. Genial, ever conciliatory Viserys hardly seems the sort to have arranged a conspiracy for murder, however, and Harwin had not in six years revealed the truth. Rhaenyra herself was the only person who could say for certain, and she maintained stalwartly that her sons were trueborn Velaryons. Indeed, Viserys stood to lose more than he gained with the conspiracy: although the decision of Lyonel to accompany his son back to Harrenhal had been unforeseen, Viserys surely must have known that his own Hand would be leaving the city temporarily, and would have been able to adjust his plans accordingly. The king, in declining health, relied on strong Lyonel heavily, yet he risked – and suffered – his trusted Hand dying in the blaze in an attempt to kill a rumor which only grew worse after the deaths of the Strongs.

The last suspect Gyldayn named (though he himself does not reveal who supported the accusation) was Larys Strong, the younger son of Lyonel, and this seems to be the most probable suspect of all. Larys stood to gain much immediately from the deaths of his father and brother. Larys was a second son, who had joined the king’s confessors when his father became master of laws but had not apparently advanced since that time. How important the king’s confessors were is not known, although the office of Grand Confessor was considered sufficiently superfluous not to be filled after the time of Daeron II; in any event, Larys did not stand to inherit a seat of his own. If matters remained as they were, Larys would have spent the rest of his life as a minor civil servant, relying on his lordly brother and the crown for support. With his father and brother dead, however, Larys inherited the greatest seat in the land: Harrenhal. Additionally, as a Strong himself, Larys would have presumably had friends, kin, and/or servants in Harrenhal itself on whom he could rely – and to whom he could give discreet, murderous directives.

What Gyldayn does not acknowledge, however, is the probable green involvement in the deaths of the Strongs. The greens had been reduced in their influence on the appointment of Lyonel Strong as Hand; with Ser Otto stripped of his chain of office for “hectoring” the King, and Viserys coming to rely on Strong, Alicent and her faction understood that a restoration of Hightower power would be, at the very least, unlikely under the current regime. Lyonel did not leave his personal views on Rhaenyra, but having gained his position from the fall of the openly green Otto Hightower, and having his son be “the foremost of the blacks”, Lyonel may well have appeared a pro-black Hand – and one who would not fight for the rights of the Hightower-Targaryens on the king’s seemingly imminent death. The Strongs may not have had the wealth of the Hightowers, but Harrenhal was still a redoubtable seat, and combined with the backing of the Velaryons (and the careful silence of Harwin on the paternity of the Velaryon princes), the blacks would have a much easier time pressing Rhaenyra’s case for succession with the Strongs in power. If some accident were to befall Lyonel and Harwin, however, Viserys could be persuaded to name Otto Hightower Hand again, Rhaenyra would lose her formidable champion, and the greens would once more be ascendant.

There were gains to be had on both the greens’ side and Larys’, and a conspiracy between the parties seems possible, if not indeed probable. Perhaps Alicent or Otto Hightower approached Larys, with an offer to name him to the small council – a position of guaranteed courtly influence and income – if Larys arranged the murders of his father and brother. Accordingly, Larys – aware Viserys had ordered Harwin back to Harrenhal – convinced his father to join Harwin in his journey back; Lyonel, who from the limited information presented seems to have had no particularly poor relationship with his second son (and no reason to suppose the son for whom he had secured a court position would betray him), took Larys’ advice. Larys may have then reached out to his contacts at Harrenhal to arrange the “accidental” fire, waiting for the news that father and son had been caught in the blaze.

From lowly civil servant, Larys would have become Lord Strong of Harrenhal and Master of Whispers to the king. Viserys debated whom he should name his new Hand, but it seems likely Ser Otto – who had performed a similar move years before, when urging for the removal of Prince Daemon from the small council – convinced the king to forgo his brother (and daughter) and look to someone with more experience – someone like, say, Ser Otto himself. The greens would benefit later from allying with Larys Strong: it was he who smuggled Aegon II out of the capital when Rhaenyra invested it, and he who arranged the taking of Dragonstone and the trap laid for Rhaenyra at the end of the Dance. While it cannot be truly known who was behind the fire at Harrenhal, Larys Strong seems a very likely candidate.

Conclusion

Throughout the main novel series, George R.R. Martin has introduced a number of murder mysteries; indeed, the very main action of A Game of Thrones is precipitated by the mystery surrounding Jon Arryn’s death. In this way, the murder mysteries in “The Rogue Prince” serve as narrative outlets in what might otherwise be classified as a “mere” historical work. By giving the reader a number of potential culprits, while leaving the truth tantalizingly unknowable, Gyldayn allows the reader to engage in the story, adding his or her own thoughts and analysis to the long-dead victims.

Additionally, the two examples of the mysterious deaths in the “Year of the Red Spring” underline the theme of heightening tension presented throughout “The Rogue Prince”. The reign of Viserys I, though initially promising, saw the increase in factional hostilities – the same hostilities which would explode into war upon the Young King’s death. These deaths, with different (and colored) sources offering various factional culprits, illustrate just how serious the political battle had become by the late reign of Viserys; the blood of Laenor Velaryon and the two Strongs would be the first, but far from the last, shed in the black-green struggle.

Thanks for reading! Questions? Comments? Find me on Twitter, and follow the blog while you’re there! Remember you can also find the blog on Facebook and Tumblr as well!

really good job on this one. I like that you braught up the greens as suspect for the fire at Harrenhal, imo they’re the only ones who gain more than they lose.

Greetings

Glad you enjoyed it! The greens certainly stick out to me as people who stand to gain by removing the Strongs. I still think Larys was involved – he stands to gain a lot as well, and it is suspect that he gets a small council position afterwards – but collaboration could work

Great! I think it was Daemon behind Laenor’s murder. Sure, Alicent wanted Aegon wedded to Rhaenyra, but with the Velaryon heirs ahead of any potential Rhaenyra-Aegon children, it was kind of pointless, as the Targaryen-Hightower line would not, in the long run, inherit the Iron Throne. If Alicent can prove Rhae’s children are bastards, then she has no need of the Rhaenyra-Aegon match; Viserys has to disinherit Rhaenyra’s line and execute Rhaenyra herself, and Aegon becomes first-in-line, future ruling king instead of Rhaenyra’s merely king consort.

I would say there are definitely arguments for both Daemon and Alicent. Both want to see poor Laenor gone, and both would know to prey on poor Qarl’s financial instability and emotional distress to work him for their ends.

Audio? You’ve spoiled us now.

Ha! Glad someone enjoys my silly voice. When I’m not on vacation I promise I’ll record this (eventually)

Your voice is great – I love the way you change if for the quotations.

Thanks! I do what I can – FWIW, doing these recordings and the podcasts has helped a lot in my ability to listen to my own voice (I can actually make it through a whole podcast episode without muting myself, where before I used to mute it anytime I heard myself start talking)

Viserys I was such a worthless king. Jaehaerys I made a blunder, I am thinking. ‘Queen who should have been’, more like.

Pingback: The Ravenry: Week of 1/11/16 | Wars and Politics of Ice and Fire

Pingback: El año de la primavera roja: ensayo sobre asesinatos misteriosos en El príncipe pícaro (1ª parte)

Pingback: El año de la primavera roja: ensayo sobre asesinatos misteriosos en El príncipe pícaro (2ª parte)